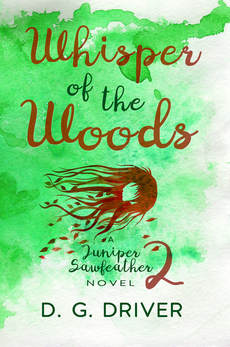

How did a class about CPR, depressing and dire as the subject may be, give me some insight about writing? It’s all in the presentation. In addition to being a writer, I’m also a teacher. I work at an early childhood development center in Nashville. I’ve been doing this job for twelve years. Every other year we have to get re-certified for CPR and First Aid, so I’ve had this same class with the same Red Cross instructor six times. I’ve seen this man go gray and gain fifty pounds over the years. (He would’ve seen me go gray too, but I dye.)  This instructor takes a very no-nonsense approach to this subject. He makes it quite clear, repeatedly, that the point of CPR isn’t to bring a person back to life. It’s to keep oxygen going to the brain until the medics arrive. He says this so we won’t feel responsible if someone dies. That’s very kind of him. The man is serious and rarely cracks a smile. He does his four-hour class without aid of a Power Point or an easel with big card illustrations. We just have a stapled handout with some instructions to keep in our classrooms in case we need a reminder. Usually our CPR class is scheduled at the end of a work day, but this time it was scheduled at 8:00 am. I anticipated being drowsy and drank an extra cup of coffee. Here’s the thing, I don’t know if it was the caffeine high or what, but the CPR man kept me fully engaged the whole time. I was riveted. You know why? He is a great story-teller. I swear to you, this man had an example for every point, and an anecdote for every example. So many, in fact, that he could derail the whole class if we asked him a question, and we had to rush at the end to finish up. I’ve heard a few of these stories before, but this year he shook it up with some new ones. He’s been in the real world of resuscitation and had some real-life moments to share with us. He also told stories he’d heard about from colleagues. Car crashes, electrocutions, drownings, and fires. Some were horrific, because he wasn’t shy about talking about blood or the reality of a situation. He wanted us to know what we might be facing if we encountered someone who needed CPR or if our hands were needed over a wound to stop the gushing blood. Yes, he deftly described the difference between dark blood that oozed from a vein and bright red blood that pulsed and arced out the body from an artery. He painted a vivid picture of why we need to evaluate the setting of an accident for danger, like live wires, furniture that could fall, or fire. If we were not going to be safe, we were not to help the victim. “Get out of there,” he insisted, trying to relieve us of feeling the need to be heroic. He said it was not helpful to the firefighters and ENT folks if we added to the list of people who had to be carried out of the scene. He then told us of a horribly sad story where the person trying to help died in the process, and then the firefighter died because he had to save two people instead of one and didn’t have time to get out of the building. Ah! It was harsh sounding, but he reminded us over and over again that if a person isn’t breathing, that person is dead. “You can’t hurt dead,” he said when showing us the right placement of our hands over the sternum and making it clear that if we did the compressions right, we would most likely break some ribs. “And if he groans or complains of pain, then stop. He’s not dead anymore. You can fix a broken rib, but you can’t fix dead.” One of the most interesting asides he had for us was when he told us that even if the person is clearly dead (and probably too far gone to be resuscitated) to do CPR anyway if there are family members present. “Make them feel like you tried and it will help the survivors to know someone made an effort to help. It’ll help your conscience, too.” The writer in me already got to work imagining this tragic scene. When can I put it in a book?  His stories and vivid descriptions weren’t all he regaled us with. He also had these crazy analogies that painted a perfect, if sometimes weirdly hilarious, picture of how the body works. For example, instead of just telling us the order of how a body shuts down when faced with an injury and going into shock, he described the body as having an electric breaker box inside. He said there is a little leprechaun in there shutting off the breakers one by one. The leprechaun knows what are the most important and least important things drawing energy out of the body. So, he shuts down the flow of blood to the appendages (fingers and toes) first, which is detectable by pressing on the tip of a finger and seeing if blood returns to the fingernail bed. Then he shuts down the skin, causing someone to go pale. Then he shuts down the digestive system because it uses too much power – why we vomit. And so it goes until all the power is going specifically to the heart and brain, the only organs that matter in the battle for life and death. He mentioned that clever and devious leprechaun so many times that by the time the class was over, I was convinced there are actual leprechauns living inside us. I named mine Sid because I’m pretty sure he’s the one wreaking havoc on my acid reflux condition. So, here’s the point I’m making. Sometimes stories are serious. Sometimes they are too “to the point” or factual. If this instructor had just come in and said, “Here’s how you do this. Here’s how you do this. Blah blah blah…” I promise you, I would have zoned out, and I would not have retained anything he said. What makes a story come alive are the details that change words from being informative sentences to words that make a connection. Adding in a character’s memory, an extra thought about how they feel about what’s happening to them, or even a strange but accurate metaphor can really spice up a scene and help the reader understand what’s happening better. At a recent speaking engagement, a teen writer in the class asked me, “How do you make your novel long enough? My book is really short.” I told her to do what this man did at my CPR training class. Fill the plotline with examples – how your character feels, reacts, remembers. In my Juniper Sawfeather Novels, I often have June flash back to a memory of her younger childhood when her environmental activist parents taught her some valuable skill during their protests that she is now putting to use. I do this show how she knows how to do something and also to remind the reader how long she’s been living this crazy life. This is from Whisper of the Woods – book 2 in the trilogy – when she is trying to get herself into a tree boat (a kind of hammock) that’s been assembled for her 170 feet up in the branches of a tree.  Deepak finished tightening the tree boat into place. When he was finished this small thing that looked like little more than a sleeping bag was dangling in the air, held in place with black vinyl straps, metal clips and rope. “That doesn’t look super safe to me,” I told him. “It’s fine. Watch.” And he gingerly lowered his body from the tree limb he’d been standing on until he was lying flat inside the boat. It looked a little like the same combination of moves to climb into a floating kayak. Thing was, I was never good at that. There was a trip to Pacific City and Tillamook Head in Oregon that my parents took me on where we were going to kayak around to coves and look for signs of pollution hurting the sea life and vegetation, and every time I tried to get into my kayak it would tip over. They both wound up having to hold it for me, and even then it tipped over before I got all the way into my seat. Eventually they told me to stay at the cabin and wait for them to get back. I was ten then. “I don’t know about this,” I told him. Does this take a pause in the action for second? Yes. But it also shows that she is not good at this particular skill, and that raises the stakes a bit. This hammock is supposed to keep her safe, but not if she can’t get into it in the first place. If she fails, she will fall to her death. The memory winds up helping the reader understand June’s trepidation more than if I’d just written, “She was nervous about getting in the tree boat.” When working on your current project, think about layers of story-telling. How can you change a lifeless “this is what happened” passage to something with a pulse? Give it a try. If it makes your story too long or is too much, you can always cut it down. You can’t hurt dead. As always, I'd love to read your comments. Feel free to post them below or add your name to my mailing list.

|

D. G. DriverAward-winning author of books for teen and tween readers. Learn more about her and her writing at www.dgdriver.com Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Author D. G. Driver's

Write and Rewrite Blog

“There are no bad stories, just ones that haven’t found their right words yet.”

A blog mostly about the process of revision with occasional guest posts, book reviews, and posts related to my books.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed