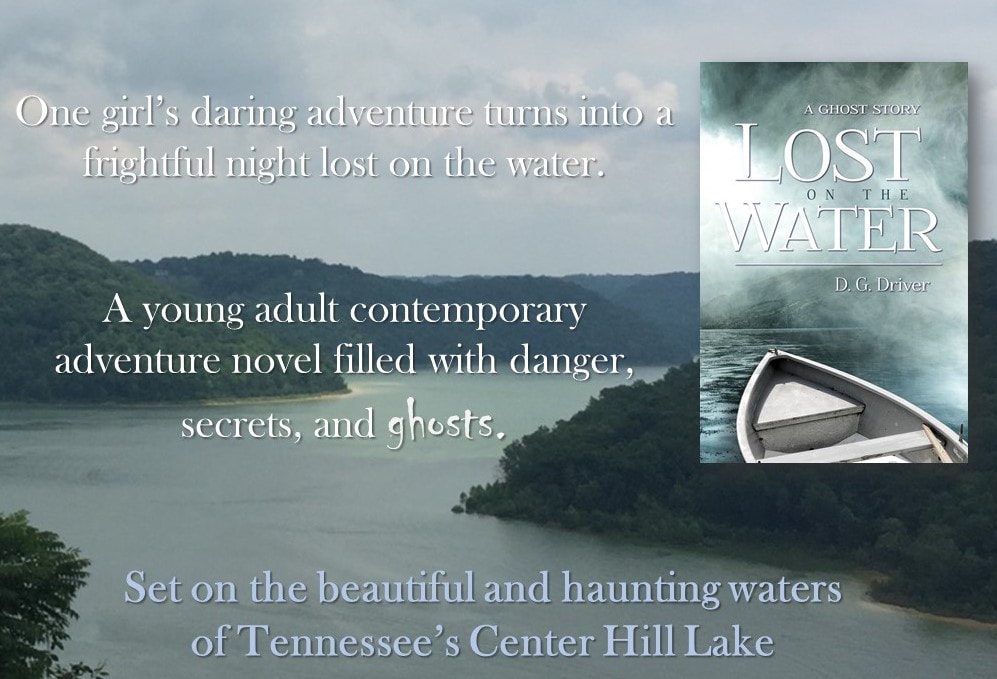

The steps of the courthouse is usually the big stage for the Bluegrass performances. The steps of the courthouse is usually the big stage for the Bluegrass performances. I was going through the listings on my TV this morning to see what would be on tonight. (I'm watching Hamilton tomorrow to celebrate the 4th of July). I saw that on the local PBS station they were going to air the annual Smithville Fiddler's Jamboree this weekend. I thought, "Oh no! Please tell me they aren't doing the Jamboree right now during Covid!" After a more in-depth search, I found out that it's all virtual this year. Thank goodness. No in-person events. This is safe, yes, but also sad. Like a lot of events cancelled this year, the Smithville Fiddler's Jamboree is a fun one. It's a craft fair centered around Bluegrass performances and competitions. It happens every year on the weekend closest to Independence Day in this small rural town near Center Hill Lake in Tennessee, a couple hours east of Nashville. I went to it one time. It was deathly hot, but it was a good time. When I was writing Lost on the Water - A Ghost Story, I remembered the quaint town of Smithville and decided to use it as the setting. I wanted it to be a summer story, so I set the beginning of the book on Sunday, July 5th, the day after the giant event ends and the world has gone quiet and still again. Today, I thought I'd share the opening chapter of Lost on the Water, introducing this little town and my bratty main character Dannie. (I promise she grows as a person.)  Chapter One THE CABIN BY THE LAKE The greatest adventure of my life happened when I was three years old, and I don’t remember any of it. According to my mother, the one and only time we visited my grandparents’ house there was some drama about me wandering off down the road and getting lost when they weren’t looking. Their house was surrounded by woods and near a big lake, so there was a great deal of panic. They found me hours later asleep on the side of the road. The way the story goes, when Mom woke me up, I told her I’d been following some boy. He was a big boy. Mom said I was specific about that, but she had no idea if it meant the boy was big in size or older than me. I didn’t have a lot of words then. I was mad at him, apparently, because he pushed me, and I fell into the dirt on the side of the road. I skinned my knee and started crying. I looked up to yell at the boy, “I don’t like that!” But a car zoomed by—fast. Then the boy was gone, and I thought he’d been hit by the car. I cried and cried until I fell asleep. My parents assured me that no boy had been hit by a car. My grandparents had no idea who the boy could have been. No one lived near them. They let it all go as the active imagination of a little girl. In the end, the incident freaked them all out so much that we never went back to visit them again. I’m still not clear on if it was my parents’ refusing to bring me back, or if it was my grandparents’ refusing to have me. Or all of the above. Whoever it was, eleven years later they finally changed their mind. Whatever was the big deal didn’t seem to bother them anymore. All worries of me chasing after invisible boys were pushed aside, because my parents decided it was perfectly fine to abandon me with Grandma for two weeks. I secretly hoped to top that previous adventure just to spite them. I’d already been brainstorming ideas to destroy a few hours of my parents’ vacation. “I can do it myself.” I lunged in front of my father and yanked my suitcase off the baggage claim conveyor. The weight of it almost caused me to fall backward, but I played it off like nothing happened. I refused to look at my parents to see them covering their snide smiles. Nothing about what I was doing was “cute” or “funny.” My desire for independence wasn’t “charming.” I’d had it with them. Two hours of traffic to Los Angeles. Two hours waiting at the airport. Five hours crammed together on the plane. I was so over “family time,” and now they were telling me it would be nearly two hours again until we got to Grandma’s house out in the country. I wanted to die. I still didn’t understand why I couldn’t have made this flight on my own. They could’ve dropped me off at the airport, and I could’ve been one of those unaccompanied minors. A bunch of my friends with divorced parents did that all the time. It would have been liberating to take this trip instead of stifling. Mom insisted she wasn’t being overprotective of me. Her reason for them tagging along with me was that she didn’t want to make Grandma drive all the way to Nashville to pick me up and have to drive back home again. It was too far, and they were asking so much of her to put me up for the next two weeks. Put me up or put up with me? I rolled my suitcase down to the car rental, and I shoved it in the trunk on my own. Dad could figure out how to maneuver it to make room for their baggage. I slipped into the backseat and plugged in my earbuds, so I wouldn’t have to listen to the country music oldies station my parents settled on. They didn’t even like country music, but this was, as they put it, “the good stuff ” because it was the Judds, Reba, and Randy Travis, the ones they remembered from their younger line-dancing days. Age didn’t make it better in my opinion. It was still all twang and steel guitars. I didn’t look out the window one single time until 50-plus minutes had passed, and my parents pulled off the freeway—excuse me, interstate—to stop at a gas station. Mom told me to use the bathroom at the gas station because we wouldn’t see another toilet until we got to Grandma’s house. I didn’t listen, and she wasn’t kidding. Forty-five minutes had passed already, and there hadn’t been any more gas stations, fast food restaurants, or even a row of trees since we pulled out of that station. All I saw were fields of grass and the occasional farmhouse. Only ice was left in my thirty-two-ounce soda cup, and now I really had to pee. “Seriously, Mom,” I squealed from the backseat. “How far into country-bumpkin land is her house? I gotta go!” “I told you,” Mom said. “That’s right, Dannie,” Dad chimed in. “She did tell you.” “Could you just pull over somewhere?” “Where?” Mom asked. I had one of those moments when I seriously wished I was a guy, so I could just make use of my empty cup. “We’re almost there. You’ll make it.” Dad pointed out the front window. “Oh, look, you can see the lake from here.” I groaned. I didn’t want to see any form of water at that moment. I kept my eyes trained on my DS, trying to concentrate on my game even though I couldn’t sit still. I missed the glimpses of big, beautiful Center Hill Lake that was geography’s purpose for this remote town in Tennessee. The car slowed and stopped. “Are we there?” “No,” Dad said. “Stop sign. We’re entering town.” “Stop sign?” I asked. “It isn’t even a big enough town for a stoplight?” From my view out the window, I could see a row of small, one-story shops with their lights off and Closed signs in the windows. A page of newspaper tumbled over itself down the sidewalk in the light breeze— the only movement around. Although the scene was in full living color, if you call drab beiges, yellows and dirty whites colors, it kind of looked like the backdrop for an old black-and-white Twilight Zone episode. There are always Twilight Zone marathons on the Fourth of July, so the images were fresh in my head. I imagined that at any second that skinny guy in the suit, Rod Sterling, would come out one of those doors and let us know we were about to enter a life-changing spook story. “Oh look!” Mom blurted out, making me jump and come way too close to wetting my pants. “How quaint! There’s a quilting store! An actual quilting store. I wish I had time to stop there.” Okay, so that was a weird comment. Come on, Rod, I thought. Come on out and explain why my mom is behaving like she’s never been here. Interrupting Mom’s reverie, what I said out loud was, “Mom, why are you acting like all this stuff is new to you? Those shops have been here a hundred years probably.” She cleared her throat but then didn’t say anything. “Mom?” My dad answered for her. “Your mom didn’t actually grow up here. And she hasn’t been here too many times.” “What are you talking about?” I asked. “Grandma and Grandpa always spoke about this place like they’ve been here forever.” A weird silence filled the car for a moment as we rolled down the street, as if they were trying to decide if they wanted to tell me something or avoid it. What were they keeping from me? I was about to bug them about it when something caught Mom’s eye and she was back to the passenger window again. “Oh! Look at all the antique shops!” “You sure you don’t want to stay and vacation here? Since it’s so charming and all?” My parents weren’t taking me to Grandma’s house for some holiday weekend. No, this was the middle of summer. A time when I should be back home in Corona Del Mar, California, riding bikes with my friends, taking the bus to the beach, having tons of fun hanging out at Fashion Island, seeing movies, playing the arcade games at the pier, and maybe taking a trip to the water park. But no. My parents were going to Paris. “That’s Paris, France, not Paris, Tennessee.” My dad liked that joke and told it about a hundred times to everyone he met between the LAX and Nashville airports. Dad had some business trip he had to go on, and he was taking Mom with him. “A chance of a lifetime,” they said. A chance of a lifetime for them—not me. “Besides,” Mom went on in her defense when she insisted I couldn’t come with them, “you would hate Paris. What would you do there? It’s full of fine art museums. Couture. Fancy food. It’s not exactly pizza rolls, video games, and skateboarding over there.” Okay, so I wasn’t exactly a fashion expert or a big fan of the pretty stuff. Let’s take my hair, for example. I kept it short-short, dirty-dishwater blonde, and never combed. In fact, I about made my mom’s hairdresser pass out when I told her I wanted “a boy’s cut.” She refused to do it, so I walked out on her. I saved up some allowance and went to one of those walk-in haircut places on my own where they gave me just the cut I wanted, trimmed over my ears, above my neck, and a touch longer on top so I had a little bit of bangs that I swept to the left. I’d been getting it trimmed every couple months ever since. I tried makeup once, but it made my face feel dirty. My figure is about as thin, gangly, and flat-chested as they come. Mom said some girls were slower to develop a figure and not to worry about it. I was concerned for a while when all the girls changed, and I didn’t. When I hit fourteen I stopped caring. My body suited me just fine. I didn’t have to wear a bra, and I certainly didn’t deal with all those stupid boyfriend problems that Jenna, my best friend, had to go through all the time. Still, not being built to look good in dresses didn’t mean I didn’t want to fly to Europe and eat some authentic pastries and good cheese and get a couple new T-shirts with French writing on them. Mom’s stance on the issue of me going with them wouldn’t budge. “I’m not buying a plane ticket and spending a fortune to hear you complain the whole time. Besides, your dad and I could use some private time together.” All right. That’s fair. But couldn’t I stay with friends at home? Jenna’s mom said it was fine with her. No. My mom had other ideas. Why don’t I have a nice visit with Grandma in Tennessee? I don’t get to see her much. Wouldn’t that be nice? She could really use the company now that Grandpa is gone. I love Grandma. She’s pretty cool. I didn’t see her often, but she’s got this really subtle Southern accent and she knows how to play a lot of different card games. Grandpa had been awesome. I remember when he built a tree house in our backyard one time when he came to visit. From scratch—not from a kit. The tree house is still standing. I still play in it. Well, not play so much as hang out in it. Sometimes. Usually by myself lately, because a lot of my girlfriends don’t want to climb up there anymore. Splinters and bugs, you know.  Well, ever since that weird incident of me getting lost, Grandpa and Grandma always came to visit us. They said it was more convenient for them because my mom had an aunt in California, and if they came out West they could visit all of us in one trip. Auntie Brenda died a few years ago, but they still insisted on visiting us and not the other way around. Grandpa died this past January. My parents went to the funeral, but they left me at home because they thought it would be “too much” for me to handle. I might not have been graced by puberty, but that didn’t mean I was a little kid. At any rate, with Grandpa gone, Grandma said she wouldn’t fly anymore and didn’t want to go far from home. Kudos to my mom for trying to get Grandma to come to our house to stay with me. She explained many times about how much easier it would be to get one ticket for her than arrange three flights for us. She bribed her with offers to send her to a spa treatment and told her any kind of food we wanted could be delivered so she wouldn’t have to cook the whole time. Grandma said no. Nothing could make her ever leave Tennessee again. Now that I was here, I wish I could understand why she felt that way. I didn’t, though. It looked boring here. Just houses and grass and a lake and a place they called a town. Apparently, they didn’t know the definition of “town” was supposed to be a place full of activity. There weren’t any cars or people visible anywhere. “Does Grandma live close to this cosmopolitan mecca?” I asked. “Cause if not, I think I see a pizza place over there that might have a bathroom.” Dad drove right past it. “She’s only a few miles from here. Just hang on.” “I can change my clothes, but you may have to pay extra for the urine-soaked seats of the rental car.” “Funny, Danielle,” Mom said. Ooh, she used my whole name to emphasize how not funny I really was. “Where is everybody?” I asked, squirming in my seat. “It’s Sunday,” she said. “Shops are closed on Sundays.” “Are you kidding me? Whoever heard of that?” Dad laughed. “It used to be like that everywhere, Dannie. Not every place is full of heathens like where we live.” Once we got past what Mom kept calling “The Downtown Square” we made a few turns and went uphill a bit. The view out my window got a lot greener. Trees popped up everywhere and there were houses instead of farms. I gathered we were pretty close to the water, because a lot of driveways had boats in them along with pickup trucks or SUVs with hitches. I saw some jet skis in one yard. I wondered who lived there and how I could get to know them. Then we broke through the little smattering of houses and continued on the two-lane road up a rise. Seemingly endless amounts of tall green trees lined both sides of the road. “Where does Grandma live, exactly?” I asked. “Well, it’s not a house, per se,” my mom answered. “It’s a cabin.” “A cabin?” I wasn’t sure if that excited me or scared me. A cabin would be a cool thing if I were with my dad and some friends going camping. I pictured a rustic, old place where we’d drop our gear and collapse for the night before getting up and starting out again the following morning for some hiking, fishing, or whitewater rafting. But as a place where I’d be wasting ten days of my life with a lady in her seventies, the word “cabin” filled me with dread about the extreme lack of activity I’d be facing. We came over a ridge, and a considerable portion of the lake came into view. It was a large body of water, but it was curvy with tons of inlets and coves forcing the water to twist and wind around them. It didn’t look like any lake I’d ever seen before. “Are you sure that’s not a river?” I asked. “Lakes are supposed to be round. Lake Arrowhead? Lake Tahoe? Big round lakes.” My dad slowed the car to a stop and pointed off to the left. “It’s a reservoir, Dannie. Way up that way is a dam that was built in the forties, and it caused the water to pool up here. It’s sixty-four miles long with almost four hundred fifteen miles of shoreline.” “That’s huge!” I said. It didn’t seem that big looking at it, but I guess I wasn’t seeing the whole thing. “How do you know all that?” “When your mom and I were here for your grandfather’s funeral, we needed a little diversion. So, one afternoon we took a tour of the dam and drove around the lake,” Dad told me. Mom piped in then. “The whole thing is taken care of by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. They own all the land around it, and there are a couple state parks for camping and hiking. You should have a good time here.” That all sounded great except that my hiking and camping buddy was going to be an old woman. So…probably not going to happen. Dad resumed driving again, and we went downhill toward the water. “If the lake is owned by the Army Corps of Engineers, whatever that is, how does Grandma have a cabin here?” “This cabin has been in my father’s family for generations, long before the dam was ever built. He managed to hang on to it, but they bought up the rest of his land from him and put some more cabins up as rental properties. During the big holiday weekends, the cabins fill up with tourists.” She gave my dad a look then, and he rolled his eyes and shrugged in response. I’m sure that all had something to do with them trying to convince Grandma to sell her cabin or use it as a rental and make money off of it. I’d overheard a lot of that from their heated phone conversations. The walls in my house are thinner than my parents think. The road turned parallel to the water, and I saw all the reddish log cabins. There were about twenty of them, all identical to one another, with nifty little front porches filled with rocking chairs. I noticed that some of the cabins looked like they had covered hot tubs out back. It seemed like a cozy place for a family trip. There was a small dock out in the water that I guessed all the renters were supposed to share, and the pebbled beach was wide and ready for families to set up chairs and picnics.  Down at the far end, this small beach gave over to the woods again, and that was where the one cabin that was different rested. It was not a log home in a neat, spiffy, cookie-cut design. This ranchstyle place was a little longer than the others, the logs rough and gray with age. Pretty flowers lined the front windows to each side of the wide front door, which was inviting and showed that someone lived there. However, I couldn’t see a path to the front door, making me suspect that Grandma didn’t want the tourists in the nearby cabins to come knocking. My parents turned into the gravel driveway that sliced a wide grassy yard in half and followed it until it curved behind the house. The gravel drive faded into a rocky, overgrown backyard marked with a dozen or more trees. It struck me as weird that Grandma kept the front yard so neat and trim, while the backyard looked avoided. Maybe it was difficult to mow around the rocks and trees, but it came across as worse than that, as if she preferred it wild and ignored. A smallish garage stood opposite the driveway from the house. I’d never seen a house that didn’t have a garage attached to it, and I thought about how inconvenient that must be for Grandma. The big green door on the front of it was down and locked with a padlock, and her car was parked on the driveway in front of it, letting me know right off the bat that the garage was not used much. At least not for her car. A long wooden deck with a hip-high railing ran along the entire back wall of her house. It was decorated with some simple furniture, potted plants and wind chimes. And there, sitting in a worn-out, upholstered swing, was Grandma waving a glass of iced tea at us and smiling. I had the door open and had jumped out before Dad fully stopped the car. “Love you, Grandma!” I shouted. “I’ll say hi in a minute, but I gotta find your bathroom.” I ran past her, into the house, and heard her call after me, “Down the hall and to the right!” I’m sure I could have figured that out. Her house wasn’t exactly big. It had a kitchen, a living room, two bedrooms and one bathroom between them. However, her directions kept me from having to think, so I did as she said. A moment later, I felt a lot better and was able to smile and think again. I returned to my family a whole different person. Except for the fact that I still didn’t want to be there. Grandma had poured everyone a glass of her “sweet tea,” and they were all seated around her picnic table. She gave me a glass, and I plopped down on the squeaky swing with the faded yellow upholstery. One sip made me gag slightly. I couldn’t believe how sweet the tea actually was. It was like drinking a piece of melted sugar cane. And though it may sound strange coming from a fourteen-year-old kid, I didn’t like it. While I listened to my parents catch up with Grandma and show her pictures from their brochures of all the places they were going to visit, I twirled the ice around in my glass until it melted. The creaking of the swing helped me tune out their voices. I’d heard all about the Louvre and Notre Dame and the Arch de Triomphe a thousand times and didn’t care to hear about them again. Somewhere in the distance I could make out a motor running. I tried to see where it was coming from, but the wooden railing of the porch was in my way. I stood up and leaned on it, gazing out at the backyard. A forest of trees wrapped around the back of the garage like a cloak. More trees stood like a troop of guards at the far end of her wild lot, attempting to block the way down to the lake. One of those many bends in the river-ish lake went right around her property. Between the trees, I could see only the tiniest swath of deep blue water from where I was standing. It was almost as if the overgrown grass and trees were purposely arranged to block my view. No matter how far I leaned forward, I couldn’t get a better angle to see more. The motor sound grew louder. I wanted to see what kind of boat it was. Then, as though someone read my mind and wanted to help me out, some of the tree branches blocking my view spread apart. It was just like if someone had grabbed them and pulled them aside for me. It could have been a breeze, but I didn’t feel one. Also, if it had been a breeze, the branches would have snapped back in place after a second. These held open for a solid moment, long enough for me to clearly see a speedboat whip by. Oh, sweet! One of her neighbors had a speedboat! I jumped over the rail and started running down to the shore to see it. But Grandma’s shrill cry made me stop in my tracks. “Dannie! Dannie, don’t go down there!” I hope you enjoyed that opening to my novel. The pictures are of the actual town of Smithville (where I've done a couple booksignings) and Center Hill Lake (where I wish I was on a boat right now). If you're intrigued and want to read more, my publisher has the book temporarily enrolled with Kindle Unlimited. The ebook is only $2.99 or you can get it for free if you're a KU member. You can also order a paperback copy at Amazon, Lulu or through the indie bookstore Parnassus Books in Nashville. Find all those links, another excerpt, and reviews here.

Have a great holiday weekend. Stay safe. Wear your mask when you go out. Leave a comment if you'd like to let me know how you're spending your holiday. Comments are closed.

|

D. G. DriverAward-winning author of books for teen and tween readers. Learn more about her and her writing at www.dgdriver.com Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Author D. G. Driver's

Write and Rewrite Blog

“There are no bad stories, just ones that haven’t found their right words yet.”

A blog mostly about the process of revision with occasional guest posts, book reviews, and posts related to my books.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed